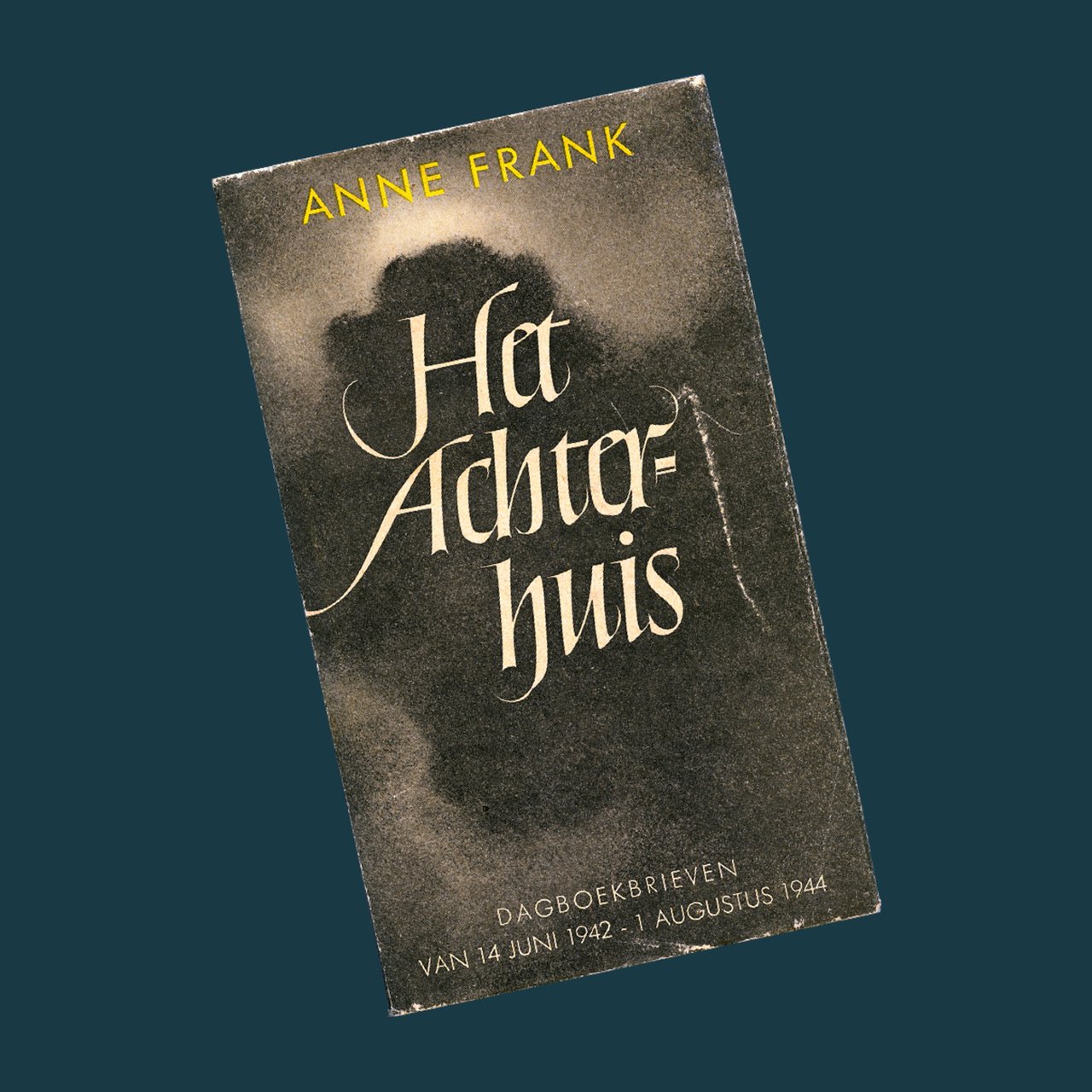

Initial reactions to ‘The Secret Annex’

Otto Frank also sent a copy to Minister Gerrit Bolkestein, who was Minister of Education of the Dutch government in exile during the war. In March 1944 he gave a radio address from London on Radio Oranje in which he called for important documents such as diaries and letters to be preserved, so that after the war what the Dutch people had gone through in the years 1940 to 1945 could be told. This appeal prompted Anne to rewrite her diary with a view to its publication after the war.

In his accompanying letter Otto wrote: ‘If this book should contribute to better mutual understanding between people then the writer did not live in vain.’

‘I will certainly read it’, wrote Bolkestein to Otto on 30 June. ‘I share the wish that you express yourself in your letter (…). But we still have a long way to go’.

Friends of Anne

In her diary Anne wrote a farewell letter to Jacqueline van Maarsen, her best friend. By this time she had been in hiding in the secret annex for several months, and could not send the letter because that would be too dangerous. But of course Jacqueline was sent a copy of ‘The Secret Annex’. She replied by return of post, saying she had opened the package with ‘mixed feelings’. Jacqueline expected that ‘it will be a success’ and was also very impressed by the foreword, written by Annie Romein Verschoor. In that foreword she compares ‘The Secret Annex’ with the diary of Marie Bashkirtseff (1858 – 1884), which was especially popular in France. ‘Who knows, Anne’s book might also be so famous!’ Jacqueline concludes. In an article in 2001 she emphasises that this was mainly meant ‘to encourage and support Otto, because I didn’t have so much confidence in it. So soon after the war nobody wanted to read more about it.’

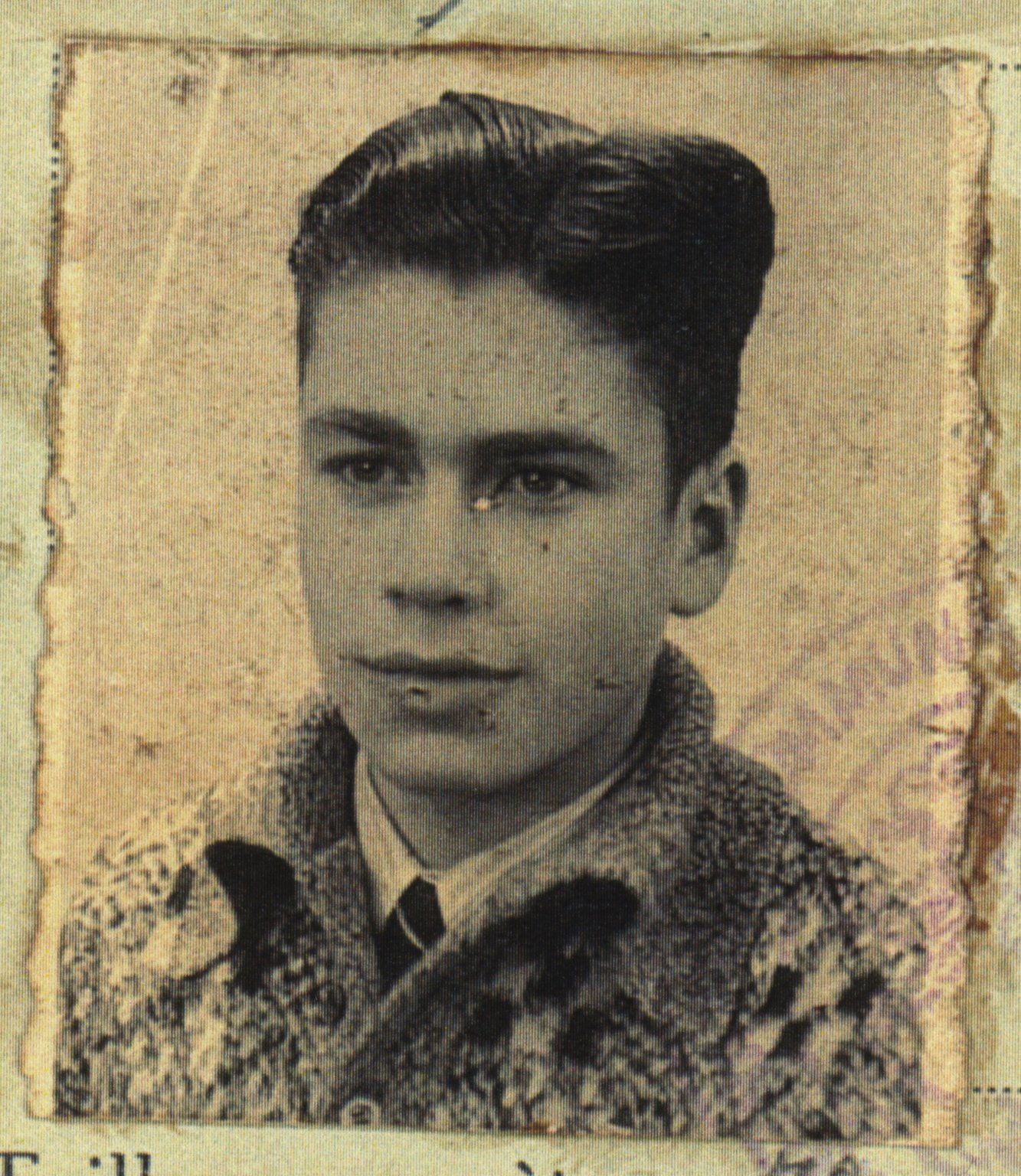

The last friend Anne saw was Helmut ‘Hello’ Silberberg. Hello and Anne got to know each other shortly before she went into hiding. He saw her for the last time on 5 July 1942, the day before she went into hiding. Hello survived together with his parents in hiding in Brussels. He was still there two years after the war, when he received a copy of ‘The Secret Annex’ there. Hello found it difficult to write to Otto.

Hello wrote: ‘Never in my life have I found it so difficult to write a letter. Even if Anne had not named me in her diary, I would have been shocked by this story. We, who ourselves experienced a ‘Secret Annex’ for more than two years, understand and compare each of Anne’s thoughts. I am convinced that I will never again know anyone who could record those thoughts so sincerely and aptly, and at the same time as an indictment against the future’.

Hello offered his help to distribute Anne’s book, and asked if there was already a French translation. He also said he wanted to come to Amsterdam to visit his grandparents, and also hoped to meet Otto. ‘I hope, dear Mr Frank, that I have been able to contribute a little to the quelling of the many too sad thoughts.’

Friends of Margot

Otto not only sent copies to Anne’s friends, but also to Margot’s. Jetteke Frijda, for example, was also immediately sent a copy. She had been in hiding, and was deeply moved by Anne’s diary letters. ‘I cannot find the words to express how this diary has affected me’, wrote Jetteke. ‘So deeply felt, and so clearly and movingly has she documented her experiences.’ Just as with Hello, the book evoked memories of her own time in hiding. ‘The terrible time in hiding, when you were so dependent and always had to look at the same faces, comes so clearly to mind, and I think only those who experienced it themselves can understand how awful that was.' But in spite of that, it is 'a fine and pure memory of Margot and Anne, which I am extremely happy about, and my friendship with Margot will always be retained in my memory as something so beautiful.’

Trees Lek also received a copy, and cherished the memories of her friendship with Margot. ‘I have read them [Anne’s diary letters] one after another in one afternoon, and will undoubtedly often reread them. Still, even without this tangible memory, I would never forget Margot and Anne. I often think especially of Margot.’

Barbara Ledermann found it much more difficult to respond. She finally sent a reaction in early September 1947. Barbara has lost her sister Sanne, a good friend of Anne, and her parents: all three were killed shortly after their arrival in the concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau. Barbara herself survived the Holocaust. She went into hiding, and had false papers. She hoped for Otto’s understanding: ‘You will understand how very difficult it is for me, and I have also repeatedly considered whether I could not write to you other than in thanks. But I cannot. After two years of struggle I have managed to accept life as others accept a religion: without understanding it. It passes over us, takes us a little further with it and then lays us down again. I don’t believe I will be particularly concerned about what happens around me or with me.’

Barbara realised that this had little to do with ‘The Secret Annex’. Her life was marked by sorrow. ‘I was also happy to find Suusje [Sanne Ledermann] in it. I miss them all terribly.’ The conclusion of her letter is sombre: ‘There is so little point in everything.’

The course instructor

During the period in hiding, helper Bep Voskuijl ordered a correspondence course in Latin from the Leiden Education Institutions. Not for herself, but for Margot Frank. Margot did the homework, and Bep sent it in. That homework was marked by A.C. Nielson. He too received a copy of ‘The Secret Annex’.

It seems that Margot was no exception. In his response to Otto he wrote: ‘During the war hundreds of people in hiding, often in the remotest places, followed our lessons. (…) I have saved hundreds of letters from this time as a precious remembrance of the many lonely and fearful people in hiding to whom my lessons brought comfort and culture in an often highly unintellectual environment. Many wrote me letters of thanks after the liberation.’ He would keep ‘The Secret Annex’ together with these letters. ‘God grant you strength in your great sorrow’, he finally wrote.

The teachers

A letter from Mrs Kuperus-De Rooij shows that Otto had people read Anne’s texts before their publication. She was the principal of Anne’s Montessori school and her teacher in the sixth grade. ‘I find it extraordinarily compellingly written’, she wrote to Otto in March 1946. ‘It is also so informative to know about her thoughts, her state of mind. I believe it must be important for anyone who is an educator to read it, because all these things can help us in the education of young people in their difficult adolescent years. I therefore sincerely hope that the publication of this book will go ahead. It is also so wonderful that Anne writes about herself there, I mean about the publication of this diary.’ When Otto actually sends her a copy, over a year later, she warmly thanks him. ‘It gives people food for thought, and gives a good insight into the psyche of a young girl. (…) You have done well to give this book to us all.’

During her time at the Montessori school Anne walked to school with Jan van Gelder, her teacher in the first to the fourth grade, and then told him stories she had made up together with her father. Soon after he received a copy he wrote to Otto: ‘The reading impressed my wife and me very deeply of the great loss that you – and I may say humanity – suffered because of her passing.’

Some teachers at the Jewish Lyceum, which Anne attended in the school year 1941 – 1942, also received a copy.

School principal Wim Elte was deeply affected. ‘I read it in one sitting. After everything we have seen of people in the camps, it is a blessing to come into contact with something good and pure – ‘The Secret Annex’ is a precious asset for us all. I remember Anne and Margot very well; Anne belonged to the large mass of the lower classes at school, with whom I didn't come into much contact; Margot stood out in the upper classes because of her splendid intellect, her sense of poise and style.’

Rosey Pool taught English at the Jewish Lyceum, and also organised cultural activities. Anne didn’t have English lessons herself, but Rosey taught English to Edith Frank. She too received a copy. ‘There may not be many among the readers who have read or will read the book as carefully as I have,’ she told Otto, ‘but I hope there will be many who will tell what it had to say to me and will therefore love it as much as I do.’

Otto Frank also gave a copy to Jaap Meijer, who taught history at the Jewish Lyceum. Jaap Meijer wrote one of the first reviews of the diary. His article appeared in the Dutch Jewish Weekly as early as 1 August 1947. He only had limited memories of Anne. ‘Among the hundreds of pupils of this school was – in the first grade, where I taught her myself for a year – a frail girl. Her expressive Jewish eyes looked brightly into the black Goles [exile, diaspora]. She barely stood out among her classmates. She seemed witty. She was talkative. A true Jewish child: Anne Frank.’ At the end of his review he concluded: ‘Meaningless and full of pain is the question of whether Anne would have become a famous writer. But even more heart-breaking is the realisation of the kind of happiness this girl could have found in a normal society. A frail Jewish child. With big eyes. Just romping and playing in the Emek [valley, plain]. Without a diary. Without sorrows. Not famous. Rather: forgotten. Not unnaturally gone.’

The royal family

In the Secret Annex Anne closely followed the activities of the Dutch royal family. When the birth of a princess was announced Anne wrote: ‘I think it’s wonderful. No one here understands why I take such an interest in the Royal Family.’ (Diary, 21 September 1942) She pasted a picture postcard of members of the royal family on the wall of her room. Her fervent wish was to become a Dutch citizen after the war. ‘And even if I have to write to the Queen herself, I won’t give up until I’ve reached my goal!’ (Diary, 11 April 1944)

Otto sent copies to Queen Wilhelmina and to Princess Juliana. In a brief reaction – just one sentence – Max Kohnstamm, private secretary to Queen Wilhelmina, wrote: ‘By order of H.M. the Queen, I express my gratitude for sending the diary of your daughter, who died in Bergen-Belsen, which the Queen has read with sympathy and emotion.’

Princess Juliana left her reply to Henny Sneller, her private secretary. ‘ Her Royal Highness Princess Juliana has asked me to convey her special thanks to you for sending her your daughter's diary. I personally had the opportunity to tell Her Royal Highness about its remarkable contents. No doubt Her Royal Highness, who is herself the mother of four daughters, will read these pure letters with warm interest and deep sympathy, in which your child showed herself as she essentially was. May this book, which gives such a clear picture of your daughter’s inner life, give you some comfort in your great sorrow.’

Libelle

During the period in hiding Anne was sometimes given a pile of old Libelle women’s magazines by helper Bep Voskuijl. She cut out pictures from them, which she stuck on the walls of her room. Sis Heyster's articles on young people and education were of particular interest to Anne. She pasted an article on blushing – 'A troublesome phenomenon!' – in her diary, and she discussed the article in detail in her diary letter of 6 January 1944.

Sis Heyster also received a copy from Otto. ‘I would so much like to have known her’, she wrote to Otto, ‘and helped her in her inner development, if she had wanted me to. She could indeed have become a strong and special woman – even if it would have cost her a hard battle with and against herself.’

Sis Heyster was one of the few people to address the events following the arrest. ‘I hardly dare to ask you how she endured the mental and physical horrors of Bergen-Belsen. I close my eyes in horror after finishing her letters.’ She would be honoured to meet Otto. ‘If you can talk about Anne, and if it would do you good to talk to me about her, then I, for my part, would be very happy to make your acquaintance.’ That meeting took place on 12 September 1947.

Bergen-Belsen

In July 1945 Otto heard from the sisters Janny and Lien Brilleslijper that Anne had died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. For Miep Gies, this was the moment to give Anne's writings to Otto. Barely two years later, 'The Secret Annex' was published. Lien too received a copy. In his accompanying letter, Otto says that they had probably known a completely different Anne. ‘I am very happy with this book and liked it very much’, wrote Lien in her response. ‘This is indeed a different Anne from the one we knew. I would like to talk to you about this again, and if you call me, perhaps we can make an appointment for you to come and have dinner with us, for example. I wish you all the best and a great deal of strength.’

The right decision

It is no longer possible to say exactly how many people Otto Frank sent or gave a copy of ‘The Secret Annex’ to. The reactions he received are full of sympathy. People also invite him to visit, to talk about it, to come for a meal, they wish him a lot of strength. The letters also show great appreciation for the diary letters themselves.

The reactions must have given Otto Frank confirmation that his decision to publish 'The Secret Annex' was the right one. Of course in 1947 he could not have imagined how well-known the diary would become and that the rest of his life would be defined by 'The Secret Annexe'.